Hepatorenal Syndrome

Hepatorenal Syndrome (HRS) is an extremely serious and life-threatening condition that affects kidney function in some people with advanced liver disease. HRS is most common among people with advanced cirrhosis (scarring of the liver) and almost always occurs in those with ascites (a buildup of fluid in the belly area associated with cirrhosis). Because of the seriousness of this condition, both the patient and caregiver need to be aware of the complications, prognosis, and treatment options. See our special section on the patient/caregiver relationship.

Types

Hepatorenal Syndrome is now associated with acute kidney injury and is called HRS-AKI. “Acute” injury means that it is sudden. The old term for this was “Type I Hepatorenal Syndrome.

- HRS-AKI is marked by a rapid decrease in kidney function and can quickly progress to life-threatening kidney failure. The kidneys, which are part of the urinary tract, perform a number of necessary bodily functions, including filtering blood to remove waste and extra fluid from the body. Signs of decreasing kidney function may include a significant reduction in urination; confusion; swelling caused by the buildup of fluid between tissues and organs (a condition known as edema) and abnormally high levels of nitrogen-rich body-waste compounds in the blood (a condition known as azotemia).

- People with cirrhosis often develop AKI that is not HRS-AKI. The most common cause of AKI is dehydration, either because of an illness that prevents drinking enough fluid, or on some occasions from over treatment with diuretics (water pills).

There used to be a type of hepatorenal syndrome called “Type II HRS”. This was meant to include people with less severe kidney injury associated with cirrhosis. More recent research has suggested that this type of kidney injury is in fact uncommon, and therefore the term is no longer used.

Cause

The exact cause of HRS-AKI is still unknown. Up to 10 percent of people with cirrhosis and ascites will develop HRS (National Institute for Rare Disorders, 2022)

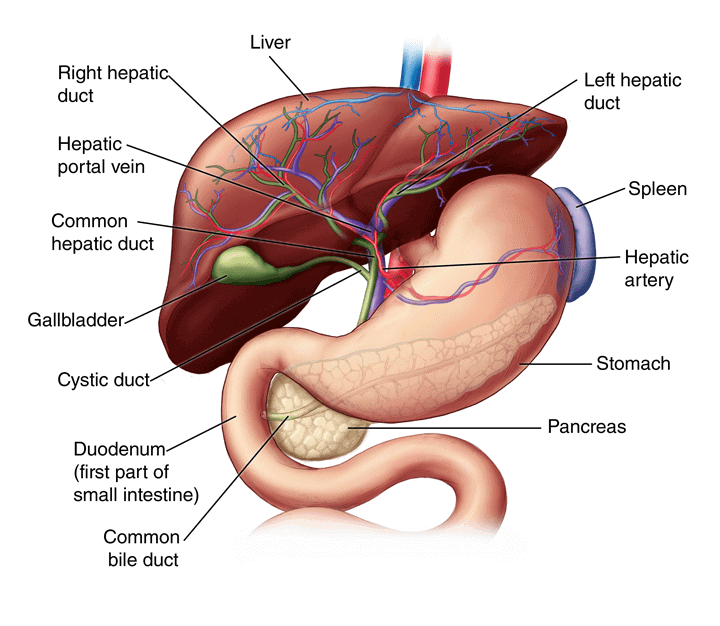

The main characteristic of HRS-AKI is a reduction in blood flow through the blood vessels that lead to the kidneys. When blood flow to the kidneys is restricted, kidney function gets worse over time. The exact cause of this reduction in blood flow to the kidneys is unknown, but some researchers believe it may result from a combination of factors, including high pressure within the portal vein, which carries blood from the digestive organs to the liver. This high pressure is called portal hypertension. The most-common cause of portal hypertension is cirrhosis of the liver.

Researchers have also identified certain “triggers” that can make it more likely for people with liver disease to develop HRS-AKI. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is one of the most common triggers. SBP is an infection of the membrane lining the abdominal cavity. Another cause of HRS-AKI is too many diuretics.

If you have cirrhosis, the following will be important to prevent Hepatorenal Syndrome:

- Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These include aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, etc.), naproxen (e.g., Aleve), and many other generic and brand name drugs.

- Avoid contrast dyes used for certain medical tests such as MRIs and CT scans.

- Eliminate alcohol intake. Patients with cirrhosis should never consume alcohol.

Symptoms

Hepatorenal syndrome has several general symptoms, including:

- Fatigue

- Abdominal pain

- Not feeling well, or overall discomfort

- Decrease in urine

People with HRS may also have symptoms related to advanced liver disease, including:

- A yellow tint to the skin or eyes (jaundice) caused by too much bilirubin (created by the breakdown of red blood cells) in the blood

- An abnormal buildup of fluid in the abdomen (ascites)

- An enlarged spleen (splenomegaly)

- A temporary worsening of brain function (confusion and/or memory loss) related to hepatic encephalopathy

Predicting the Possibility of Hepatorenal Syndrome: The Liver/Kidney Connection

There is no specific test to diagnose HRS-AKI. However, one test that can indicate that Hepatorenal Syndrome may be occurring is a lab test for serum creatinine. Serum creatinine is a test that measures how well the kidneys are working. It is normal to have creatinine in the blood. If the level becomes too high, though, it can be an indication that the kidneys are not working well.

There is a general range for normal creatinine on lab tests, but there can be things that affect the readings. For instance, creatinine readings can be affected by a person’s muscle mass and body size. The ranges differ for men and women. In general, “normal” ranges for creatinine would be:

- Men: 0.7 to 1.3 mg/dL (61.9 to 114.9 µmol/L)

- Women: 0.6 to 1.1 mg/dL (53 to 97.2 µmol/L)

It is important to know what your creatinine level is early on in medical testing. That way, if or when things change, there will be a way to compare the original number to the increasing number and to monitor how quickly any changes are happening.

Therefore, all patients with cirrhosis and ascites should have their blood creatinine checked on a regular basis, and very frequently if on diuretics, and especially if the dose of diuretics has been increased or if a new diuretic has been added. Having serum creatinine tests done and monitored by an expert physician - and receiving appropriate treatment - can affect a person’s survival time.

The serum creatinine test is not the only way HRS-AKI is diagnosed, but it is an important test that anyone at risk for HRS-AKI should discuss with their healthcare providers.

Diagnosing Hepatorenal Syndrome (HRS)

Because there is not a single test to confirm HRS-AKI, a final diagnosis would be made through a complete medical evaluation. Because the diagnosis of HRS-AKI can be very difficult to make in some patients, any patient suspected of having HRS-AKI should be seen by an expert, preferably a highly experienced hepatologist who has previously managed many patients with HRS-AKI. Doctors would take a detailed patient history and order various tests to learn whether certain conditions exist. These conditions include advanced liver failure with portal hypertension.

Past history and additional tests are also done to rule out other causes of kidney damage. Other possible causes might include:

- Previous urinary or kidney disease

- Bacterial infection

- Shock (a sudden drop in blood flow through the body)

- Recent treatment with certain drugs that affect kidney function, or so-called nephrotoxic drugs

- Urinanalysis – physicians routinely examine the urine carefully; in patients with HRS-AKI, there is little if any evidence of inflammation or acute damage to kidney cells

The International Club of Ascites, an organization that encourages scientific research in the field of advanced liver cirrhosis and its complications, has developed specific criteria for the diagnosis of HRS-AKI.

Treatment for Hepatorenal Syndrome

Here is a helpful video about treatment for Hepatorenal Syndrome: https://alfevents.org/poster-competition/support-2023/#dannykwon.

The first goal when considering treatment for HRS-AKI is to try to improve liver function and prevent kidney injury. Doctors carefully monitor patients with HRS. They often try to address the underlying cause of liver disease. In addition, certain steps would be taken to address any kidney injury that has taken place. At the first sign of any kidney problem doctors would be expected to have their patients stop taking their diuretics and to avoid NSAIDs and other medicines that could further injure the kidneys. Doctors also watch for infections and treat them if they occur.

Depending on a patient’s individual situation, medications may be given to improve blood flow. Albumin is one treatment, and it may be combined with others to provide the best chance to stabilize a person with HRS.

Medications can be useful for people with HRS, but current guidelines suggest that liver transplantation is likely the best treatment. The decision to consider liver transplantation must be made by an experience hepatologist, typically in concert with a nephrologist, a surgeon, and the entire transplant team. Some people may be too ill and medically unstable to undergo transplantation.

A treatment that is often considered for treatment of HRS-AKI is renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis). There are several types of dialysis, and this treatment removes waste, salt and extra water from the body and performs other functions normally done by healthy kidneys. Patients with HRS-AKI are typically candidates for only certain types of dialysis.

People with evidence of kidney injury should be advised by their medical team to avoid diuretics (which can worsen kidney function), promptly treat infection, and maintain their electrolyte balance. The major electrolytes in the body include sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and chloride. Medical providers can determine electrolyte levels with a few tests and recommend how to best address any imbalance.

People affected by HRS-AKI, particularly those needing dialysis or suffering from advanced kidney failure in the months leading up to a planned liver transplant, may also need a kidney transplant. Even after a successful liver transplant, kidney problems may continue, sometimes requiring dialysis.

Other options for people who are unable to get a transplant or who are awaiting one include:

- Medications to increase blood pressure that is too low

- Albumin to improve kidney function

Clinical trials are research studies that test new treatments for people with various illnesses. You can find more about clinical trials at the bottom of this page and speak to the doctor to find out if clinical trials might be right for you.

The Patient and Caregiver Experiences

If the Hepatorenal Syndrome (HRS) occurs, it can be frightening and confusing for patients and their caregivers or loved ones. If the patient’s health worsens, they will almost certainly be admitted to the hospital and, depending on the situation, placed in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Many medical tests would be performed during this time. If ascites is present, fluid would be drained. The amount of fluid can vary, but often several liters will be removed through a procedure called paracentesis. Medications mentioned above would also be provided.

It is common for people who are hospitalized with HRS-AKI to feel very weak, tired, and possibly unresponsive to those around them. If the liver is not working well, a person’s skin and whites of the eyes may look yellow. This is called jaundice. They may lose muscle mass, and if they are able to move around at all, they may need a lot of assistance and be at risk of falling.

While in the hospital, a person will be seen by several types of doctors. HRS-AKI requires care coordination between a liver specialist (hepatologist or gastroenterologist) and a kidney specialist (nephrologist). HRS can be life threatening, so the immediate goal is to stabilize patients with the use of medications and starting them on kidney dialysis. Dialysis will do some of the work normally performed by healthy kidneys. This care coordination within the hospital may continue for months, depending upon the circumstances.

A person with HRS-AKI may eventually require a liver and/or kidney transplant. In fact, even though there are treatments available to help people with HRS-AKI, transplant is the ultimate goal for most of them. However, a person must be medically stable enough to undergo a transplant. It is also important to note that even when a person is approved for transplant, there is a waiting list and it may still take time for a match to be found – Liver Transplant: What You Should know

What Caregivers and Patients Need to Know

If liver disease and HRS-AKI progress, confusion can occur. People with HRS may have difficulty understanding information presented during medical appointments, or they may forget valuable information that they were told by their health care team. This may be due to the syndrome itself but can also be due to feeling overwhelmed by what is happening. It is advisable that anyone with advancing liver disease have a caregiver, family member, or friend present during medical discussions so that there is a better chance of understanding test results and care plans. When dealing with any medical condition, having two sets of ears in the room can lower the chance of missing information about a disease, treatment choices, and other important details. Having a caregiver or loved one present during appointments is almost always helpful not only for the person with the disease, but also to those who are closest to them and are assisting with their care.

Caregivers or those within the patient’s support network can often be the eyes and ears of the patient. They may want to ask questions to their medical team or get clarification about treatment and it’s purpose. It is fine to take notes, this can be helpful later if certain details cannot be recalled easily. Depending upon when a person may be released from the hospital, at-home care may need to be arranged. There may be visiting nurses or other home care professionals who can be called in to assist with medication management and at-home monitoring of the patient’s vital signs and overall health. Caregivers can check with the patient’s insurance company to see what services may be covered. It is important to note that caregivers must be either listed on the insurance policy or given permission to access the patient’s insurance information.

Patients with HRS – AKI may be eligible for palliative care as well. Palliative care means that treatment for a chronic illness can be provided, along with comfort care measures. Palliative care can be provided within medical settings as well as at home. A palliative care team consists of doctors, nurses, dietitians, social workers, nondenominational chaplains, and others who help oversee care, assist with medication management, and provide emotional and spiritual support to the patient if desired. The emotional support services are also extended to the family members and those within the support network too. For more about palliative care, visit https://liverfoundation.org/resource-center/palliative-care/.

Outlook for Anyone Living with Hepatorenal Syndrome

The outlook for people with cirrhosis and liver failure is much worse if they develop HRS-AKI. Most patients die within weeks of the onset of renal (kidney) failure without therapy. In fact, 50% of people die within 2 weeks of diagnosis and 80% of people die within 3 months of diagnosis.

Early detection is critical. People affected by HRS-AKI have a higher chance of survival if the condition is diagnosed early; they receive prompt medical treatment for kidney impairment. Again, a liver transplant may be an option depending on a person’s individual medical situation as well as the availability of a liver for transplantation. A living related liver transplant may also be an option. Helpful information for caregivers can be found at https://liverfoundation.org/resource-center/caregiver-resources/.

Questions to Ask the Doctor

- Am I at risk of developing Hepatorenal Syndrome? Why or why not?

- Can you explain what creatinine is and what it has to do with my liver and kidney function?

- Will you be checking my creatinine level? How often?

- If my creatine level gets higher, at what point would you be concerned about my kidney function?

- Is there anything I can do to lower my chances of developing Hepatorenal Syndrome?

- Can you please review what medications I can take to prevent Hepatorenal Syndrome or to help control it?

- Should I seek assistance for home health care? Will I have any special needs that could require a visiting nurse or other medical professional?

- If I develop kidney injury, would I have to go to a specialist to discuss treatment? Could you refer me to a kidney specialist if that happens?

- Would I need dialysis if my kidney function gets worse?

- Is liver and/or kidney transplant appropriate for me? Why or why not?

- What is my prognosis (outlook) for survival?

- If my prognosis for survival is poor, should I consider palliative care or hospice care? Can you please explain the differences between these types of care?

- If I want to begin palliative or hospice care, how do I start the process?

Search for a Clinical Trial

Clinical trials are research studies that test how well new medical approaches work in people. Before an experimental treatment can be tested on human subjects in a clinical trial, it must have shown benefit in laboratory testing or animal research studies. The most promising treatments are then moved into clinical trials, with the goal of identifying new ways to safely and effectively prevent, screen for, diagnose, or treat a disease.

Speak with your doctor about the ongoing progress and results of these trials to get the most up-to-date information on new treatments. Participating in a clinical trial can be a great way to contribute to curing, preventing and treating liver disease and its complications.

Potential new treatments are being studied. You can learn about privately and publicly funded clinical studies of treatments for Hepatorenal Syndrome (HRS) and other conditions at the National Institutes of Health’s clinical trials finder or by clicking here.

Last updated on July 8th, 2025 at 04:11 pm