Crigler-Najjar Syndrome

Crigler-Najjar syndrome (CNS), named for the two physicians who first described the condition in 1952, John Crigler and Victor Najjar, is a rare, life-threatening inherited condition that affects the liver. CNS is characterized by a high level of a toxic substance called bilirubin in the blood (hyperbilirubinemia).

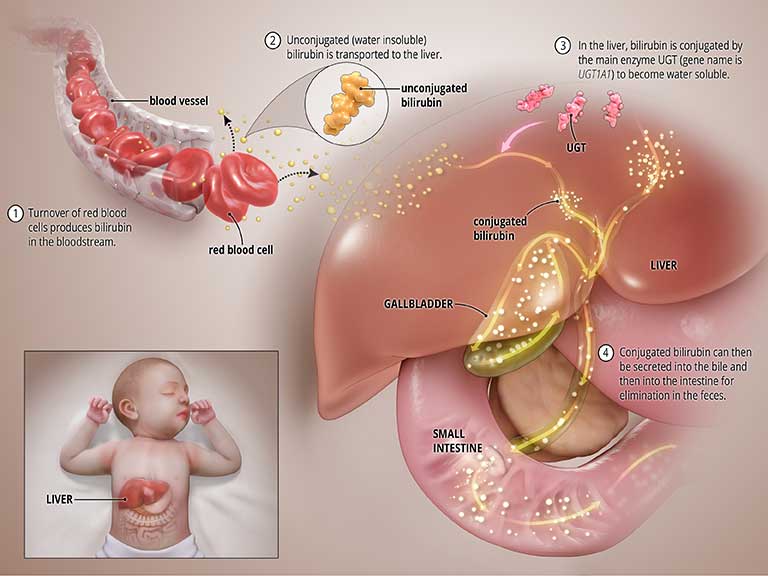

Bilirubin is produced during the normal process of breaking down of red blood cells. In order to be removed from the body, bilirubin goes through a chemical reaction in the liver where an enzyme called uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) converts the toxic form of bilirubin into a soluble form (a process known as “bilirubin conjugation”) that can be eliminated from the body through the bile and into the intestines. See the graphic titled Normal State below.

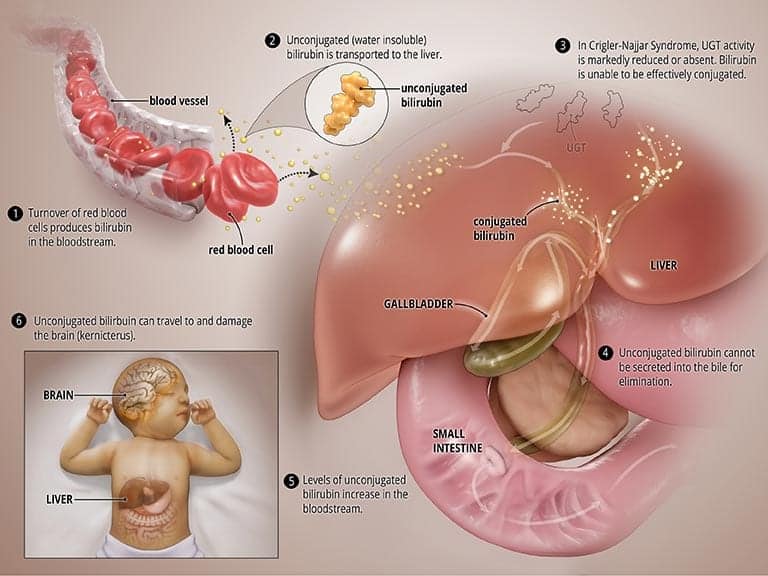

In CNS, the UGT enzyme is either completely inactive (CNS type I) or severely reduced (CNS type II). In both types, bilirubin is not broken down properly and cannot be excreted into the bile. High levels of unconjugated bilirubin accumulate in the blood and this leads to jaundice and may travel to the brain and result in a severe form of brain damage called kernicterus (more on this below). CNS type I, in which the body produces no, or very little, UGT is much more severe and can result in death in early childhood. CNS type II, in which the body produces moderate but reduced amounts of UGT, is less severe, less likely to cause kernicterus, and patients may respond to some medications. See the graphic titled Abnormal State below.

What causes CNS?

CNS is caused by a mutation in the UGT1A1 gene that is responsible for the UGT enzyme in the liver. It is autosomal recessive, which means that the baby must inherit a damaged UGT1A1 gene from both the mother and the father in order to be affected. When this happens, the production of UGT is either eliminated (CNS type I) or greatly reduced (CNS type II), which leads to the build-up of bilirubin in the blood.

If only one parent passes down the gene, a child may be affected with a less severe condition known as Gilbert’s Syndrome.

Who is impacted by CNS?

It is estimated that less than 1 in 1 million newborns are affected with CNS worldwide. Because of the genetic nature of the condition, both parents must carry the mutation in order for their child to be affected.

What are the symptoms of CNS?

The symptoms of CNS type I generally become apparent shortly after birth. Affected infants develop severe jaundice, a yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes and whites of the eyes. These symptoms persist after the first three weeks of life.

Infants are at risk for developing kernicterus, also known as bilirubin encephalopathy, within the first month of life. Kernicterus is a potentially life-threatening neurological condition in which toxic levels of bilirubin accumulate in the brain, causing damage to the central nervous system. Early signs of kernicterus may include lack of energy (lethargy), vomiting, fever, and/or unsatisfactory feedings. Other symptoms that may follow include absence of certain reflexes (Moro reflex); mild to severe muscle spasms, including spasms in which the head and heels are bent or arched backward and the body bows forward (opisthotonus); and/or uncontrolled involuntary muscle movements (spasticity). In addition, affected infants may suck or nurse weakly, develop a high-pitched cry, and/or exhibit diminished muscle tone (hypotonia), resulting in abnormal “floppiness.”

Kernicterus can result in milder symptoms such as clumsiness, difficulty with fine motor skills and underdevelopment of the enamel of teeth, or it can result in severe complications such as hearing loss, problems with sensory perception, convulsions, and slow, continuous, involuntary, writhing movements (athetosis) of the arms and legs or the entire body. An episode of kernicterus can ultimately result in life-threatening brain damage.

Although kernicterus usually develops early during infancy, in some cases, individuals with CNS type 1 may not develop kernicterus until later in childhood or in early adulthood. Patients in whom the blood bilirubin concentration is maintained at safe levels by exposure to light (see below under treatment) can develop kernicterus at any age if the light treatment is interrupted or the patient is affected by other illnesses.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 is less severe than type 1. Some people have not been diagnosed until they are adults. Affected infants develop jaundice, which increases during times when an infant is sick (concurrent illness), has not eaten for an extended period of time (prolonged fasting) or is under general anesthesia. Kernicterus is rare in Crigler-Najjar syndrome type II, but can occur especially when an affected individual is sick, not eating or under anesthesia.

How is CNS diagnosed?

Severe jaundice within days of birth may lead to suspicion of Crigler-Najjar syndrome. This may be confirmed by clinical evaluation, family history, genetic and laboratory tests. For example, blood tests would reveal a high level of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood or a lack of conjugated bilirubin in the bile.

Genetic testing to identify mutations in the UGT1A1 gene can also confirm the diagnosis.

How is CNS treated?

The primary goal of treatment for Crigler-Najjar syndrome is to reduce the amount of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood as rapidly and consistently as possible. This is accomplished in different ways for CNS type I and CNS type II.

CNS type I is primarily managed by phototherapy, in which the child is exposed to blue LED light in an apparatus similar to a tanning bed. The light bypasses the need for conjugation, and breaks down the unconjugated bilirubin, which can then be excreted into the bile and intestines for elimination. However, phototherapy is a tedious process, requiring 10-12 hours of therapy per day. The prolonged exposure to light causes the child’s skin to thicken, increasing the need for a more intense phototherapy regimen. The need for phototherapy significantly impedes quality of life.

Liver transplantation is a potentially life-saving treatment for Crigler-Najjar patients. A new liver has the enzyme with the ability to convert unconjugated bilirubin (that is unable to be excreted from the body) into conjugated bilirubin (that is able to be excreted from the body).

Patients still have the gene mutation causing the deficiency of glucuronyl transferase and can still pass the abnormality to their children.

Although some individuals with CNS type II may require phototherapy during episodes of severe hyperbilirubinemia, most are well controlled on daily treatment with phenobarbital.

What is the prognosis for someone living with CNS?

With proper treatment, patients with CNS type II can live a relatively normal life.

Unfortunately, those with CNS type I have a much tougher time, with the risk of severe and irreversible brain damage, and the only treatments available lose the effectiveness as the child ages, making the need for a life-saving transplant and search for alternative therapies much more urgent.

What is the future direction for research into CNS?

Ongoing research for Crigler-Najjar syndrome include efforts to design therapies to replace the missing or deficient enzyme. Gene therapy clinical trials, in which the abnormal UGT1A1 gene in CNS individuals is replaced with a normal UGT1A1 gene so the body can make functional UGT, are currently underway. Gene therapy could be a permanent, life-long cure of this disease if proven to be successful in clinical trials. Researchers are also investigating whether putting normal liver cells into the CN liver could provide enough enzyme to correct the UGT1A1 deficiency. However, this “transplantation” of healthy liver cells would require lifelong immunosuppression, similar to conventional liver transplantation. More information on current clinical trials can be found using our convenient Clinical Trial Locator, or at www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Patient Stories

Search for a Clinical Trial

Clinical trials are research studies that test how well new medical approaches work in people. Before an experimental treatment can be tested on human subjects in a clinical trial, it must have shown benefit in laboratory testing or animal research studies. The most promising treatments are then moved into clinical trials, with the goal of identifying new ways to safely and effectively prevent, screen for, diagnose, or treat a disease.

Speak with your doctor about the ongoing progress and results of these trials to get the most up-to-date information on new treatments. Participating in a clinical trial is a great way to contribute to curing, preventing and treating liver disease and its complications.

Start your search here to find clinical trials that need people like you.

Last updated on August 16th, 2023 at 12:20 pm